The ‘discovery’ phase of any digital undertaking is vital as it lays the foundation of any successful project. Unfortunately like many lessons from agile and the service design world it seems like a desire for a uniform, measurable approach in some organisations is creating obstacles to the technique being as impactful as if could be.

The GDS Service Manual does seems to contradict itself somewhat →

A short phase, in which you start researching the needs of

your service’s users, find out what you should be

measuring, and explore technological or

policy-related constraints.

It seems to me people get hung up on short phase.

Turn the page though (metaphorically) and you get this →

What to find out in discovery

In the discovery phase you need to understand and map out the user journey.

You should find out:

• who your users are

• your users’ needs and how you’re meeting them, or any needs you’re not meeting

• which services currently meet your users’ needs and whether they’re government services or private sector

• how you’d start developing a new service if your discovery finds there’s a user need for one

• the people you need on your team for the alpha phase

• what the user journey for someone using your proposed service might look like

• how you might build a technical solution given the constraints of your organisation’s legacy systems

• the policy that relates to your service and how it might prevent you from delivering a good service to your users

Which depending on problem in front of you might be anything but short.

I prefer this from the Australian Digital Transformation Office on the topic→

There’s no one-size-fits-all duration for a Discovery,

however, many teams spend between four and six weeks.

I think that is more realistic — especially once an organisation becomes more digitally mature and starts to have a better understanding of users and their needs (a real understanding backed by research rather than anecdote) but for some time initially there is a lot to learn and often years of misconceptions to shake off. This is not a short phase.

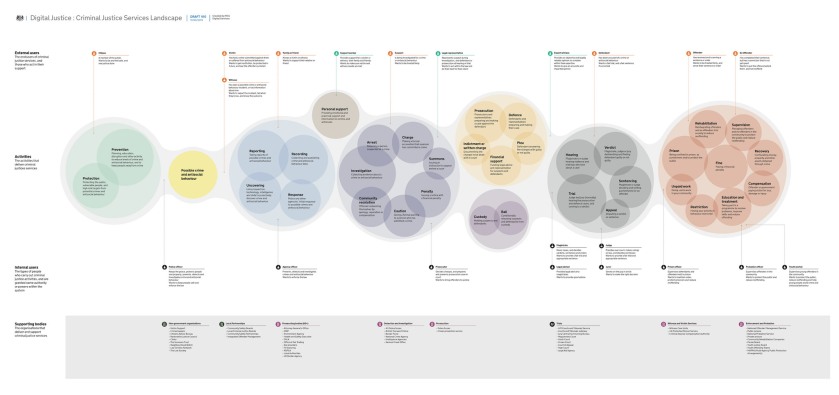

Sometimes the ‘discovery’ has a wide reach. One of my favourite pieces of work over the last few years was this massive service mapping exercise from the Ministry of Justice that span out of their ‘discovery’. To understand any one part of the journey they first had to understand the big picture.

Here is another interesting example with a great team spending eight weeks looking at how the UK border effects trade. The findings from this ‘discovery’ was that they needed to do additional — more specific — discovery work.

On the other hand Sarah Prag suggests an experienced, mature team can “rattle through (discovery) in a week or two” in the right circumstances.

Like our antipodean cousins say “there’s no one-size-fits-all duration for a Discovery”.

I think rather than get hung up on timeframes we should think about the ‘minimal viable discovery’ to get started (because that is all this is — enough information to get started — you should never stop learning about your users and should be prepared to course correct as you learn more — other wise we are just playing at being agile.)

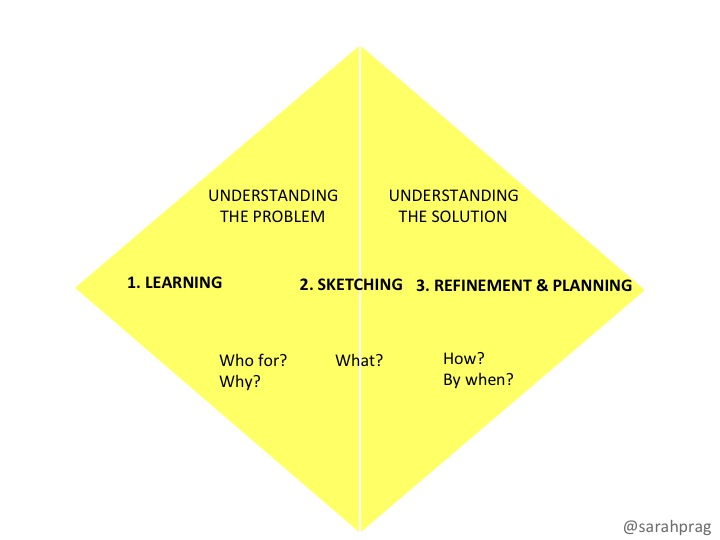

Personally I like to be able to confidently answer the questions in Sarah’s diamond (below) but your mileage may vary. Maybe you want answers to all the GDS questions above, or the DTO version or maybe even the Design Council ‘double diamond’ technique. As long as you learn what you need to learn to move to the next phase with confidence then it takes as long as it takes — whether that be two weeks or twelve. Don’t rush understanding your users — getting that right will underpin everything you do from that point on.

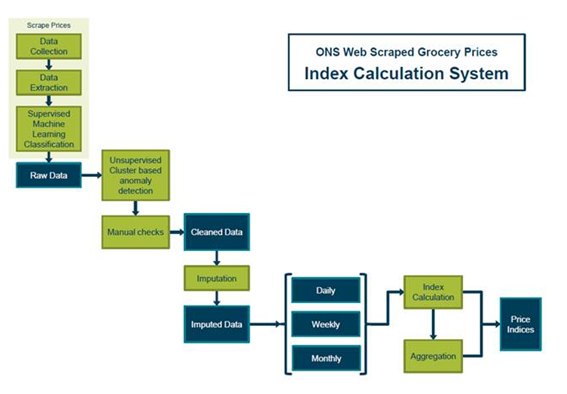

The growth of online retailing over recent years means that price information for many goods and services can now be found online. Web scrapers are software tools for extracting these data from web pages. The Big Data Team has developed prototype web scrapers for three online supermarket chains: Tesco, Sainsbury and Waitrose, which have been running since June 2014. These scrapers were programmed in Python using the

The growth of online retailing over recent years means that price information for many goods and services can now be found online. Web scrapers are software tools for extracting these data from web pages. The Big Data Team has developed prototype web scrapers for three online supermarket chains: Tesco, Sainsbury and Waitrose, which have been running since June 2014. These scrapers were programmed in Python using the

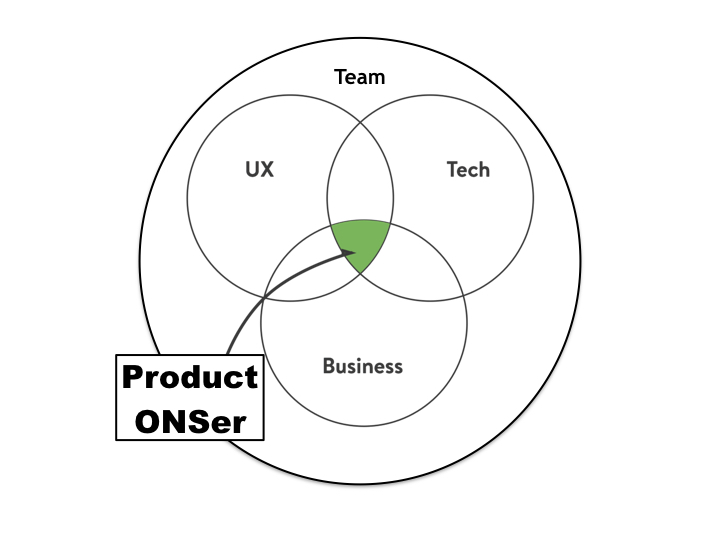

Prior to the ONS I worked in various digital and product roles at the BBC, most recently as product manager working for the

Prior to the ONS I worked in various digital and product roles at the BBC, most recently as product manager working for the  As Digital Service Manager for Electronic data capture I need to build on the great work that’s already been achieved, to deliver and run a world-class digital service based on user needs. The service covers digital products for respondents to manage and complete their questionnaires, securely message ONS and access support, as well as products to allow ONS staff to build digital questionnaires, manage how they are sent out, and support respondents to provide accurate data on time.

As Digital Service Manager for Electronic data capture I need to build on the great work that’s already been achieved, to deliver and run a world-class digital service based on user needs. The service covers digital products for respondents to manage and complete their questionnaires, securely message ONS and access support, as well as products to allow ONS staff to build digital questionnaires, manage how they are sent out, and support respondents to provide accurate data on time.